Updated July 3, 2010

One of the first surveyors of the Hathaway prairies, William Darby, predicted that agricultural pursuits might eventually be attempted, but the sterile land was good only for grazing cattle. Fifty years later, geologist Eugene W. Hilgard conducted a scientific survey of the Calcasieu prairies and found nearly the same results as Mr. Darby; however, Mr. Hilgard speculated the soil was suitable for rice farming, and he was right.

Rice farming on the prairies of Hathaway is a story that came from the backs of men, to the power of the equine, to the combustion of an engine. The industrialization of rice arose from plowing with a team of the four-legged to the four-wheeled tractor; from the scattering of seeds, then to the drill, and on to the airplane; from the reliance on rainfall, to the steady supply of water from the canal, to the reliability of the deep well; from cutting with the sickle and the cradle, to the thresher, to the combine; from curing in the “shock” to the more reliable drier; from collecting the harvest in burlap sacks to rice carts; from the stacks in warehouses to wooden, then steel cylinder bins; from hauling with a wagon, to the train, to the truck. Since farmers on the Hathaway prairies and others in Southwestern Louisiana have entered the competitive food supply market, they have constantly embraced new technology and processes to improve their endeavor and this innovative spirit continues today.

Providence Rice

Growing rice on a commercial scale in the United States began in South Carolina in 1685. Twenty-five years later, South Carolina was producing 1.5 million pounds of rice, and a decade after that, more than 20 million pounds. Although innovative techinques were introduced by African slave labor, the upsurge in production came from the increase of the number in bondage, not from innovations in planting (with the exception of flooding land using gates to catch fresh water pushed upriver by Atlantic tides) or the mechanization of the harvest. Because the processes for producing rice in South Carolina remained labor-intensive, the door opened for Louisiana when the workforce was emancipated. The open land and the completed railroad in South Louisiana allowed the experienced, progressive wheat farmers from Iowa and Illinois to grow a farming empire in Louisiana that has brought prosperity to the Rice Belt of the Bayou State for over a century.

The rice industry in Louisiana began shortly before the Civil War on the Mississippi Delta in the southeastern parishes of St. Charles, Jefferson, Plaquemines, and Lafourche parishes. The farmers there took advantage of new steam technology to pump water from the Mississippi River over the levees to their fields. But after the Civil War, as in South Carolina, rice production declined rapidly. Only a few areas in the Mississippi Delta continued to flourish.

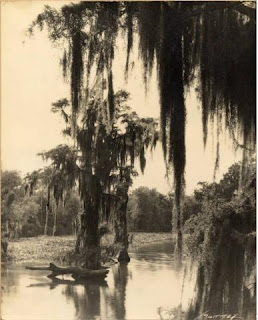

About the same time, Acadians were continuing their migration across the prairies into Southwestern Louisiana. The first Acadians out of New Orleans moved to the prairies to raise cattle. Some Acadians became cattle men and grew their holdings, but most were farmers who were content to grow their families. Acadian migration was mostly for the subsistence of their close family in small, quite, patriarchal settlements. When family settlements grew large, segments of that family would move westward on the prairie to form a new settlement.

For their new settlement, Acadians generally chose to live along the treelines of rivers, bayous, and gullies that ran in a southwesterly direction on the Pleistocene plain from the Mississippi River. They chose the treeline because the thick vegetation indicated that land was fertile. They grew small patch crops like rice, sweet potatoes, cotton, and corn. Farming was not an enterprise for Acadians; it was a survival skill. They toiled for their families and neighbors. Another purpose for their toil was for bartering and trade. Much of their economy depended on bartering. Acadians did not come from a society based on money.

Before 1880, the first Acadians moved to the prairies of Hathaway and lived along Bayou Nezpique and the Grand Marais. Some did venture away from the thicket of woods to farm where they found low-lying areas along a gulley or marais. (Keep in mind that the landscape of the Hathaway prairies was much different before 1900: dredging of the bayous and draining of the marshes and gullies did not start until the early-1900's and land-levelling was not a common practice until the 1940's.) When a farmer found the right lay-of-land, he built a split rail cedar fence around a small plot (usually 5-acres or less), and planted rice. After the seed was sown, they waited. If rice grew, it was harvested. If not, there was always next year. Dependence upon the providence of nature, and not a man-made irrigation system, gave this method of rice culture the name, “Providence rice.”

When farmers planted rice on the small plots, they sowed the seed by broadcast (scattering seed by hand on the surface). After the seed was sown, farmers ran cattle or horses into the small fenced area to trample the seed into the mud. Another method of growing rice was to dig trenches about three feet apart and keep them filled with water. But this method was labor intensive and the yield was low (at about 6 barrels per acre) because the water supply depended on seasonal moisture.

To increase the amount of water for their small fenced plots, farmers began to build levees in gullies to block run-off and flood low-lying areas. Farmers also dug ditches from those reservoirs to get the water to other nearby low-lying fields. The levees had limited success because the reservoirs were shallow and the small amounts of water that were collected often evaporated off quickly. Flooded crops from these conditions made about 10 barrels per acre.

The early farmers in Hathaway harvested rice with their hands and their backs bent using a sickle. As plots went to several acres, farmers switched to a “grain cradle.” The cradle had several blades that swept down on the grain and laid the stalks down in a row for easier collection. Another advantage of the cradle was that it could be swung while standing straight. Once the stalks were cut and gathered, they were tied into bundles, also known as “sheaves.” The sheaves of rice were stacked in a cluster called the "shock." The stacks were left in the field for two weeks (12 to 14 days) to dry, also known as curing.

To cure properly, the bundles had to be stacked in a tight cluster with the heads together. The stacks were about three feet high. Then a bundle with it’s bottom spread was laid over the top to cover the grain with its own grain facing north. Stacking the bundles in this certain fashion gave the harvested rice maximum protection from the sun and rain. Nonetheless, up to 30 per cent of the crop could be lost to improper shocking or mildew. A rainy harvest season could spell doom for the crop. Farmers determined the shock was ready for threshing “by ear,” using their judgment, and even their neighbors’ judgment on the condition of the stalks and the heads.

After the rice had dried, it had to be thrashed, which means the grain had to be removed from the stalks. Before mechanized threshers, farmers removed the rice from the stalks under the hooves of oxen or horses or they flailed a double-handful of stalks over an open barrel until all the seeds were beaten off the straw. Then the chaff was removed from the rice kernel. The job for removing the chaff usually fell to the younger boys; although this process was used by housewives who prepared smaller quantities for individual meals.

To remove the chaff from the rice kernel, the process first involved a hollow stone or piece of wood where a mortar was used to crack the chaff and grind it from the rice kernel. For larger quantities, the stone and the wood became too small for the job, so a larger pestle was made by standing a short log on its end and hollowing out the other end into the shape of a bowl. For the larger pestle, the mortar was increased to the size of a wooden bat that had two oversized, elongated bulbs at each end. For both the stone pestle and the log pestle, the mortar was pushed against the bottom of the hole or bowl to loosen the chaff. To clean the chaff from the rice, the contents of the hole or bowl were emptied into a basket. Then with great skill, the rice was winnowed, which involved tossing the rice kernels into the air, letting the chaff blow away in the wind, and the clean rice fell back into the basket.

After rice production was industrialized, the quantities continued to surge and manual labor could not keep up; then came the home mill, which mechanized the pestle using a heavy wooden pounder instead of a slim pestle. The pounder was tied to the end of an eight-foot beam which sat on a fulcrum four feet from the pounder. By stepping on the other end of the beam and quickly releasing the foot, the pounder delivered a heavy blow. Then the foot stepping on the beam was replaced by rigging the beam to an “over shot wheel.” In Roman times and in other rice cultures, the over shot wheel involved a moving stream to power the wheel from above. This wheel was powered by horses tethered to a drive wheel around a vertical axel that turned a gear system that powered the over shot wheel.

The Birth of the Rice Industry in Southwestern Louisiana

The story of the industrialization of rice in Southwestern Louisiana, and on the Hathaway prairies, began when the Northerners arrived. They found a different kind of farmer than from where they had come. The Acadian farmers were not wired for industry, or to look for ways to improve the certainty of their crop, or to increase the efficiency or volume of the harvest. The Acadians had no experience with a cash crop. They came to the prairies of Hathaway with the vast experience of self-preservation. They did not seek to make their work easier to increase productivity. They were a quite society that lived off the land and sustained their lifestyle by living in close proximity to other family members, spending much of their time with family, and toiling for the needs of their family. The Northerners' knowledge was a result of years of experience. Once the knowledge of the cash crop was shared with the Acadians, many joined in its pursuit.

The Northerners came to the prairies of Hathaway with the experience of harvesting wheat as a cash crop. They applied their knowledge to make the prairies of Southwestern Louisiana more productive than the prairies they left in the Midwest. The Northerner's knowledge depended on a scientific method: When crops came in, data was collected, and if something was not quite right, they conjured a theory to know why, and what they could be done to improve their crop the next season.

An article in the October 10, 1895 edition of the Jennings newspaper exemplifies the kind of thinking that Northerners applied to their crop to figure out the root cause of a less than stellar rice crop.

Some of the rice is very light and chalky--little more than chaff; while other crops have suffered from the ravages of insects. The light and chalky rice is believed by some to be the result of the unusually hot weather during the heading season, and conditions seem to support this theory, as very poor rice is reported where an ample water supply was had throughout the season.

With this knowledge and experience, farmers could not control the temperature during heading season. But this experience would help them better predict what the hot weather would do to their crop. With this knowledge, they could find a way to improve the possibilities of a better crop in those same conditions. The most important asset for increasing production is knowledge of what hinders production, and finding ways to combat those hinderances. Some ways were successful, some were dreadful, but the experience was valuable and could be used to make better crops in the future.

One of the most important Northerners to arrive was Sylvester L. Cary in 1883. He is important to the industrialization of rice because he took it upon himself to recruit other experienced "cash crop" farmers on the possibilities of Southwestern Louisiana. After he arrived, he conducted several crop experiments to find that rice culture was the best pursuit. Land companies also brought their own agricultural experts down to survey the land. Dr. Seaman K. Knapp, who settled in Sherman, now Iowa, recommended rice. The clay "hardpan" soil on the Calcasieu prairies was retentive of moisture, making the prairies perfect for flooding, which is perfect for growing rice.

Some of Cary’s early recruits came in 1884, and the path toward mechanized rice production was begun. Maurice Bryan, a farmer from Iowa, moved to the area with a twine binder that he had used in farming wheat. Maurice Bryan was born in Westbury, Sommersetshire, England on April 30, 1854, when Napolean III was Emperor of France. When he was 16 (in 1870), he moved with his family to New York. He married Lillian Simmons of Skaneatles, New York in 1877 at the age of 23 (the same year of General Custer’s Last Stand). The next year, Bryan and his wife moved to Iowa to give farming wheat a start. Within a few years he had joined a farmer’s association that followed the promotions of S.L. Cary and moved to Southwestern Louisiana. They formed an Iowa colony in Raymond on homestead land. He lived in Jennings for a short time, and then moved to his five-acre farm in the Raymond area to begin his new venture in farming.

Mr. Bryan had tried to use the binder in the rice fields but soon encountered too many problems in the mud. He then set out to conquer the problem of bogging and a slipping drive wheel. First, he bolted lugs made out of two-by-fours to the flat steel drive-wheel to dig into the mud. Second, he added spades to the wheels to dig into the mud when the wheel hit the ground. These additions gave the sickle, reel, and canvasses more consistent power. One other interesting note about Maurice Bryan was that he was one of the first to bring Holstein cattle to the area.

The binder was a machine fronted by a reel that spun several long, horizontal bars between two spindles outward from the top and back inward at the bottom. The spindle was turned by a pulley system attached to a drive wheel. As the spindle turned, the bars leaned the stalks of rice into a cutting sheer. The cutting sheer had two pieces. The bottom piece had pronged teeth that corralled the straw and the top piece was a blade that moved back and forth across the prongs slicing the stalks. Because the reel was coming inward toward the machine, the stalks were leaning back when they were cut and they fell onto a canvass that was rotating around two pulleys that delivered the stalks up to a blocking device that gathered the stalks as they were cut and tied them up with twine when enough was gathered. As each bundle was tied, it was lifted into a storage shoot then released when the bundles numbered from 9 to 13. These were released to field hands that arranged them into the proper “shock” arrangement.

When the William Deering Co. shipped 300 of the modified binders to Lake Charles in 1886 at a retail price of $265, large scale rice farming was born. The 6-foot wide cutting device harvested 8 acres in a day, doing the work of 16 men. Four years later, farmers from Southwestern Louisiana ordered six hundred rice harvesters. By 1900, there were 4500 twine binders in use in Southwest Louisiana. In 1917, a small engine was added to the binder to drive the sickle and binding apparatus. Then all the team had to do was pull the binder, not generate torque for the sickle. The binder remained unchanged until it was phased out in the 1940’s when the combine was introduced.

With the capacity to cut more rice, farmers soon needed more efficient plowing and planting mechanisms, as well as water to increase their yield. First were the implements. Larger plow configurations were needed to increase the amount of land that could be planted. By 1890, the wheel gang plow was being used to cut land 22-27 inches wide. These plows could break two-and-a-half acres a day. The land was stirred with a square-tooth harrow before and after seeding. The theory was to plow deep, level and crush lumps, then pack the soil. Then in the first decade of the Twentieth Century came the two and three furrow gang plow, the riding gang plow (i.e., the four horse plow).

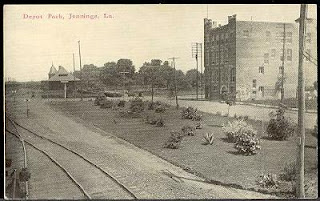

From the 1890's to the 1940's Louisiana was the highest rice producing state and was ranked either third or fourth through the 1980's. In 1890, it was estimated that more than four hundred car loads of rice were shipped out of Jennings. To demonstrate the contributions that Hathaway and the surrounding prairies made, by the late 1980's, Jeff Davis Parish accounted for 16% of Louisiana rice production.

William Henry Perrin provided a glimpse of the rice industry in 1891, when he authored

Southwest Louisiana—Biographical & Historical. In it he wrote:

The editor of the Jennings Reporter gives some figures on the acreage of rice planted in that part of the parish. He estimates that between Lake Arthur on the south to China post-office north of Jennings, and between the Mermentau River, the Nezpique and Grand Marais, there will be about nine thousand acres planted in rice, which, at ten barrels per acre, will give 90,000 barrels of rice, and of this amount he expects 60,000 barrels at least or about four hundred car loads to be shipped from Jennings. Two years ago only twenty-six car loads were shipped from Jennings; last year one hundred car loads. All this rice, should Jennings not get a rice mill, would eventually find its way to Lake Charles and shipped northward on the Kansas City, Watkins & Gulf Railway. This is only a small portion of the rice acreage of this parish, and every bushel raised in the parish should be hulled on mills here instead of being shipped to the New Orleans mills.

Says the [Lake Charles] American on the same subject: There is, perhaps, no section of country better adapted to rice culture than the lands of Calcasieu. Rice culture is now attracting more attention than any other field crop. This cultivation is simple, consisting principally of planting and flooding, and the profits are large. Had we the space, we could give numerous instances of persons making enormous profits.

Mr. R. Hall, of Cherokee, Iowa, purchased one hundred and sixty acres of land for $800. Paid out for improvements about $450. Total cost of land and improvements, $1250. He rented the land for one-third, which was planted in rice, and realized for his third of rice $1500.

J.W. Rosteet reports on twenty-one acres of land planted in rice. He gives the expense of ditching, levees, fencing, planting and harvesting at $457.68. He sold his rice for $860, leaving a balance of $462.32.

In the early 1890’s, a mechanism was developed to move away from broadcasting seed by hand. The seeder distributed seed more consistently over the field by dropping seed onto a flat, spinning wheel that threw the seed out in even patches. The wheel was powered by a chain-drive that was geared to the back axel of a wagon. The seeder could seed 25 acres-a-day, using about one sack of seed every three acres.

There’s an old farmer’s saying that “a silk purse cannot be made from a sow’s ear,” in other words, good rice must come from good seed. Good seed was free from weed seed. Honduras rice was the first type of rice planted by farmers. Then, agriculturalist, Seamann K. Knapp brought seed back from Japan. Seed from Japan could better withstand the milling process. Up until World War II, the process was to save the seed from the better looking lots that entered the warehouse.

Now with the capacity of the binder to cut more rice, and the ability to spread more seed, there was a need for a more reliable water source. The Providence method could produce a large crop, but this was too speculative for the large-scale farming envisioned by the settlers from the Midwest because rainfall amounts varied from year to year. Farmers needed a consistent source of water that provided enough to cover the growing acreage that the mechanization of rice farming had brought.

Opening the Flood Gates

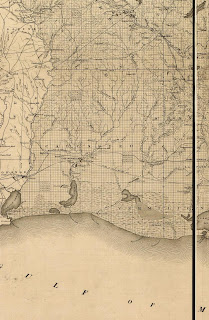

There was plenty of water in Bayou Nezpique. A.D. McFarlain, a founding settler of Jennings, built a small canal to irrigate his farm. The idea caught on and canal companies began to organize, secure the right-of-ways, and build levees. The first canal operation in the area was Riverside Canal Company in 1895. Soon construction of the Grand Canal and the Tip Top canal were under way in the Hathaway area. By 1899, there were 25 irrigating canals in Acadia, Calcasieu, Cameron, and Vermillion; nearly 400 miles of main canals, plus as much in lateral canals. Canals were built 40-60 feet wide, 4-5 feet high. The first canals were built from the outside with plows and graders; after the turn of the 20th Century, canals were built from the inside, which prevented grass and weed growth in the canal during the off-season.

A field is flooded when rice grows to six to eight inches high. The field is flooded to three to six inches and kept there until the rice matures. Levees are used to equalize water levels. An outer levee surrounds the field with inner levees making smaller fields within the larger field. The flooding process filled the field next to the pump first, then cut the levee to have as much going to the next field as being pumped into the first filed, and so on.

Levees were built, first, with a shovel. Then farmers were using a ditcher (gang plow), then a grader, by 1915. The grader was made of two 8-foot long beams in a V-shape pulled by oxen, and later a tractor. Early planters built levees at right angles to the slope of the land. They built higher levees in low areas and vice versa. This would result in water a foot deep on the low side and a few inches on the high side. This resulted in different maturity and lower yields. In time, crooked levees were built to follow the contours of the land to hold water at an even depth over the entire field.

Land-leveling came in the late-1940’s. Before fields were leveled, farmers had to deal with low knolls that dotted Southwest Louisiana. These lumps of land were about 30 feet in diameter and as high as three feet. To flatten these knolls, farmers began by taking a tractor with a dozer blade to the lumps, then running a 60-foot land plane over the field about four times. Level-land moved farmers from 5-7 barrels per acre to 20 barrels. Leveling also made water distribution, amounts of water, and levee building much more efficient.

The first canals were powered by gravity moving water with about a half-foot per mile excavation. Main canals were built on high ridges of farms. Canals had gates that opened to lateral canals on the high side of farms. Then the steam engine came along, which was capable of raising 90,000 gallons of water per minute from the bayous. The first rigging for moving water from a bayou to the fields was done near Crowley on Plaquemine Bayou by the Father of Artificial Rice Flooding, Myron Abbott. Steam pumps fueled by wood were common until the 1920’s. These steam pumps required high maintenance and were dangerous. A vigilent attendant had to monitor the pump around the clock to insure the proper water level was maintained to prevent the engine from exploding. In the 1920’s, pumps powered by “crude oil” were installed. These engines required vigilance to keep them running, but they would not take lives if mistakes were made.

Thrashing

Faced with better planted seed producing more matured rice and the capacity to cut and shock that rice more efficiently, farmers needed more than a pestle and mortar to prepare rice for the mill. Farmers again looked to the William Deering & Son concern for a mechanical device that would remove the rice from the stalk. Mechanized thrashing, also called threshing, was not new to harvesting grain. Wheat threshers had been used by farmers in the Midwest for decades. In 1889, with a few modifications, Deering built and shipped twenty-two railcars to Lake Charles loaded with threshing machines.

Because threshing machines were expensive, individual farmers would leave the threshing to a custom operation that travelled from farm to farm. Farmers contracted with the threshing operation, usually paying with a percentage of the crop and a crew was organized. Many were free labor by men who worked in exchange for free labor when the threshing crew came to their fields. The host farmer was responsible for hospitality, and that farmer's wife usually had help from the wives of several other farmers on the crew. The first threshing machine to serve the area arrived in Lake Arthur and belonged to Mr. St. Germaine and Mr. Gauthier. In the early-1900’s, the farmers in the Hathaway area had two threshing operations, both family run, the Havenars and the Fruges. When moving from farm to farm, these crews resembled a train because of how one machine was hitched to another.

The thresher was a large contraption that separated the grain from the stalks and chaff, then bagged the rice for shipment to the mill. The machine was parked in a field and farmers from the area brought their shocked rice to the machine for separation. A driver would pull his wagon, and later his truck, up alongside the machine. From the wagon, he pitched the stalks up on top of the machine. Atop the machine was a canvass that rolled into the machine. As the stalks fell off the canvass on to an iron grate inside the machine, a drum pounded the stalks into a grate. The straw continuing off the canvass on to the grate pushed the beaten straw onto a canvass that fell into a shoot. In that same shoot was debris and bits of straw that fell through the grate with the rice. It fell past a stream of air, which blew the debris horizontally and the rice fell on through. This process served the same function as the winnowing basket. The shoot emptied the straw and debris from a spout about six feet above the machine. The air in the shoot came out with enough force to shoot the straw and debris into a haystack about 20 to 30 feet from the machine.

To be threshed, the bundles had to be dry, otherwise the machine would get clogged, which would cause the belt to come off the pulley, causing further delay. Threshing usually began mid-morning after the fog had lifted. Rain usually caused a delay of several days. If the bottom of the bundle was too soggy, then that part of the bundle was cut off before fed into the machine. Another tactic for keeping the stalks dry and the machine from getting clogged was to move the shocks to higher ground.

On the threshing machine, sacks hung on a rail at the spout where separated rice flowed. When full, the sack was unhooked and a new one placed in front of the spout; then the full sack had to be sewn quickly by a skilled sewer with a six-inch needle usually sewn and marked while the next bag filled. The mark was usually a number that was used to divide at market among the shares in the crop held by the threshing crew, the canal company, and the landlord (if the farmer rented the land). By the 1920’s, 200 to 500 sacks (ranging from 160-200 lbs) per day could be threshed. Although, rice was stored in burlap sacks, farmers measured their crop in "barrels." This standard of measure was first adopted in South Carolina rice production in 1714. Farmers still use the term today.

The entire binding and threshing operation usually required 25-30 men: (1) The binder required two men—one to drive the team or tractor and one to operate the binder; (2) Three or four men followed the machine to prepare the shock; (3) Nine to twelve wagons were used (each with a driver) to move the shock from the fields to the stationary threshing machine. The threshing machine had an engine man, a separator man, two sack draggers, one sack sewer, and an extra man or two.

Planting Innovations

With a more dependable water source and mechanized reapers and threshers, farmers could increase the acreage they planted. For this increased acreage, farmers also wanted to increase their yield per acre. To improve their yield, a more consistent rate of growth in the stand and maturity of the grain was necessary. Broadcasting seed left a lot of seed on the surface or in hoof marks, which caused variances in growth and maturity at harvest time. The need to cover more acreage and for a way to plant seeds more consistently led more farmers to use the disc drill.

The drill had been in use for centuries by Chinese farmers and made its way to Europe in the 1700's. In 1841, a practical seed drill for grain was patented. Over fifty years later, farmers planting rice in Southwestern Louisiana began using them to plant rice. But the inconsistency of stalk growth was not solved until the drill was equipped with a roller to follow the disc drill and flatten the earth over the seed.

A report on the rice planting season in the June 4, 1894 edition of the Jennings newspaper exemplifies the challenge for rice farmers of the 1890's on the prairies:

Planting will continue up to July 1, but there will not be the acreage planted now that there would have been had the spring been favorable for early planting. The rice in many fields will make a very uneven stand owing to some of the rice coming up early, while the remainder is just sprouting. The finest and most even stand of rice is seen where the fields were rolled. It came up very even, made a steady growth through the dry spell, and since the late rains is the most encouraging looking rice on the prairie.

The first drills for rice had 6 spouts arranged behind an axel that supported a trough to hold the seed. Two horses pulled the drill implement. For each drill, two discs were set in a V-shape to a desired depth with a spout laid between the discs to drop the seed into the crease cut by the discs. Later models had rollers that followed the drill to cover the seed after it was planted. By World War I, 12 spouts were common, and some drills had as many as 16 spouts.

To Market

When night fell, a farmer came in, put on a clean shirt and drove the team and a string of wagons to sit in long lines at the warehouse. Here the bags of rice were unloaded by a crew and stacked in a slot rented to the farmer away from the chances of rain waiting to be milled. In the 1920’s, when trucks became common place, Model-T flat bed trucks could carry 18-20 sacks of rice. Then the Model-A trucks arrived, which could carry 40 sacks, depending on the condition of the ground.

In the 1860’s, several rice mills were built in New Orleans to accommodate the harvest coming in from the southeastern Louisiana coastal parishes. With the opening of the railroad in 1880 across the southern prairies of Louisiana and the ensuing surge in rice production, many rice mills were built to accommodate the incoming rice. By 1888, thirteen new rice mills had been built in New Orleans, and near the same number had been built across southern Louisiana on rivers with access to the Gulf, including a mill in Lake Charles on the Calcasieu River.

At the mill, rice was fed onto a rotating canvass that was gritty enough to rub the soft covering of the kernel into a fine dust, thus giving the rice a polished finish. Rice mills were built. The first mills were built in Lake Charles. Crowley also had a mill. In 1899, the first and only mill was built in Jennings by George Hathaway & Associates, which was almost immediately sold to the Louisiana State Rice Milling Company. This mill was called “The Northern Mill” by the owners and the public, alike.

Some of the larger farming operations built a home mill. Others who had held back a few bags of rice used a miller who set up shop to mill a few bags of rice at a time in exchange for a portion of the rice, which then became merchandise sold to the general public. People did not pick up their rice at a store in a plastic bag. Instead they stopped by the mill shop.

As with most industry, buyers and sellers began jockeying for the best price. Rice millers were the buyers and they soon joined forces to dictate the price paid for a crop of rice. Farmers were the sellers and they would counter the millers’ squeeze by holding their crops in the warehouses until the price was acceptable. The same types of battles continue today. Some years, the price had nothing to do the miller's trust. The season was a major determinant as well.

In the October 10, 1895 issue of the Jennings newspaper, and article entitled "The Crop Will Be Short," ran advising farmers on their best strategy:

The rice crop of Southwest Louisiana will be quite large, but it will not exceed, and we doubt if it approximates that of the 1892, which is from a quarter to a half million bags short of what it has been estimated at during the season. In view of these facts it will be well for the farmers to guard against rushing their crops to New Orleans and over-crowding that market. The domestic crop will fall far short of the amount required for domestic consumption and there is no reason why the planters should not realize the price equal to the cost of importing the foreign article. Past experience teaches that planters will never realize this much in New Orleans or any other market if shipments are such as to glut that market. If you ship to the city and your rice goes in store there are heavy expenses for sotrange insurance, etc., that must be met. You not only save this by keeping your rice at home but you are in a position to take advantage of the other markets that are reaching out in this direction for trade. Let our shipment be gradual. Don't glut the market; it don't pay.

Irrigation—Deep & Grand

Once a few canals were up and pumping, it became apparent that there was much more farm land than could be reached by canal. Many acres of farmland had to be supplied by another source. Irrigation wells were common in the Midwest to water crops, but those crops did not require the volume needed to flood rice. The Chicot aquifer was discovered about 125 to 200 feet below the surface and, in 1898, Jean Castex, Dr. Remage, S.L. Cary, and Maurice Bryan were among the first in the Jennings area to dig deep wells. In only five years time, thousands of acres that would have remained grazing land outside the reach of canals became cultivated land because of the deep well. Early wells sank 150-175 feet with four clustered four-inch pipe wells that united at the top and pumped to flood 500 acre fields. Deep wells were still not altogether reliable.

The first canal company in Hathaway was the Grand Marais Canal Company. It was later bought by the Jennings Irrigation Company, which later changed it’s name to the Grand Canal Company, which then became Louisiana Irrigation and Canal Company. When the canal was being built, the engineer and laborers made their headquarters at the location of Relift Sixteen, which is less than a mile north of Hathaway. The abandoned remnants of the pumping station still stand today along Highway 26. Here the company operated a rooming house for its workers and other help and a barn for the horses and mules that helped pull the graders that lifted the levees into place. There was also a general store and a saloon here too. The Grand Canal was built from Bayou Nezpique, beginning with a huge inlet that met a huge dual-pump station that pushed water into the canal onto the prairie westward for about two miles, then curved in a north-northwest direction for about a mile, bending westward again toward Relift Sixteen. At the relift, the canal made a ninety-degree turn that headed in a south-southwest direction for another mile, then bending straight south. In 1927, a westward extension from Relift #16 was built.

By 1901, over 500 wells had been drilled, and the next year wells were then being drilled to depths of 230-260 feet with a single, 10-12 inch pipe to irrigate 250-450 acres. Deep wells were not without problems. Sand clogged pipes and caused long delays. Different configurations were tried to keep the pipes from clogging, but after a year or two, those wells were stopped-up with sand. Then came the Getty screen and sand was no longer an issue. Fred I. Getty’s invention made deep wells successful. He was a pipe outfitter and driller who expanded his oil field drilling operation into a first-rate water drilling operation.

Deep wells had a substantial up-front cost and pump maintenance was ongoing, but the deep well proved well worth the investment in the long run. The process of pumping water and delivering enough water to flood hundreds of acres was a costly venture, and the companies that brought the water to the fields had to turn a profit. Until 1906, all profits from canals went into expanding the canal system. But, for more than 10 years, investors were not seeing a return on their investment. Much of the business was conducted by handshake agreements, but too many people were defaulting on their agreed shares for the canal companies. In 1906, those canals companies gave notice that written contracts would be required for delivery of water. The terms of the contract required a flat-rate from the farmer to turn over two bags of rough rice per-acre-watered. Even though the farmers were getting the same water, the price of that water did not hit the farmers equally. For example, a farmer with a bumper crop paid less than a farmer with a low yield per acre. In 1910, canal companies then moved to the 1/5 share of the total crop.

Canals had their risks as well. In 1902, 1904, 1931, and 1951, canals also had several instances of salt water inundation from the Gulf that reached as high as the Grand Canal. Many crops were ruined. Finally, in 1951, the locks were built to make the marshland fresh water and the salt water problem was solved. Rice farming enjoyed a great balance between water supplied by canal or by well: But many farmers would soon realize that in the long run, the expense of digging a deep well was the smarter business decision. For Southwest Louisiana in 1902, 48,600 acres were supplied by well, 323,000 by streams, and 16,000 by both. But by 1946, there were 250,000 acres supplied by well, 245,000 by stream, and 30,000 by both. More and more farmers began to break from the canal company and drilled their own deep wells. By the early-1960’s, the pump at Grand Canal was shut down and Relift #16 was abandoned.

Tractor Pull

In 1916 came the first fuel (kerosene) tractor. It was the Moline-Universal one-man tractor to be used for plowing, harrowing, planting, cultivation, and harvesting. A binder pulled by a tractor could harvest 20 to 30 acres a day. Soon the Fordson and the Waterloo Boy arrived. These tractors cost $885 in 1917 and could plow over 400 acres, averaging 8 acres-a-day, pulling a 3-bottom, 26” disc plow. Tractors were rated by horsepower at the drawbar and at the belt. In 1918, a tractor could run 12 horsepower at the drawbar and 25 at the belt. The tractor engine could run the belt in a stationary position, which could power equipment like a threshing machine. By this time, tractors were common-place in Southwestern Louisiana. From that point, harrow and plow design improved exponentially to meet the capabilities of the horsepower pulling them. In 1927, an extension shaft was added to the tractor to retire the small engine that powered the sickle in the binder.

In the 1930’s, tractors and plows improved to make twenty to thirty acres-a-day possible. The peg-tooth harrow, and four to six foot disc plows were the norm. All implements had iron wheels and rims. The back wheels were larger than the front wheels like the tractors today, but instead of rubber tires, the wheels had different-shaped lugs attached to them for traction in the mud. These tractors were tearing up the newly paved roads. Rubber tires did not come until 1945, after the war. Goodyear made a rubber tractor tire suitable for the muddy rice field, and although the transition was gradual, the asphalt roads were soon saved.

Modern Rice Farming Begins

In 1945, scarce labor and steepening wages created new opportunities for innovation. Interestingly, part of the farm labor shortage during World War II was supplemented by German prisoners of war in 1943 and 1944. Camps set up throughout Southwest Louisiana parishes, including Jeff Davis Parish. Camps varied in size from 150 to 500 prisoners. Work was voluntary. 15-20 worked for small wages under military guard. The soldiers worked surprisingly better and faster than normal labor. Most of the German soldiers in Jeff Davis Parish were from General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps (Jeff Davis News, Oct. 12, 1943).

The major innovations that helped farmers find help in the fields were the combine to cut rice and the airplane to plant seeds. Using combines to harvest rice was more efficient than the binder and it removed the need for a thresher. Planting by air only required four people—the pilot, the seed loader, and two flag men at each end of the field.

Combines had been in use in California since the mid-1930’s. The first combine in Southwestern Louisiana was purchased by Joe Pettijean in 1939. The detractors of the combine did not like that the machine left no haystack for shelter and forage for cattle. But the lift of rationing on manufacturing materials lifted after World War II and the high demand for labor, the combine made some headway. In August 1943, 8 combines were sold in Jeff Davis Parish for one thousand dollars.

The first combines were tractor drawn with a 6-foot blade. They required a loop around the field be cut to start. By 1945, combines were now self-propelled, costing about four thousand dollars with a 12-foot blade. By 1947, 60 % of the harvest was done by combine in Jeff Davis Parish. By 1950, the entire industry was converted. Design improved to prevent bogging and for the maneuvering of levees.

Combines harvested rice “green” with no need to shock the rice. Instead, rice driers were built. When binders cut rice, the moisture level of rice was 20-30% and shocked dried the rest in two weeks. Combines allowed no curing period. Cut rice at 20% moisture. Rice was prone to spoilage with so much moisture. The rice had to be dried down to 12%. Rice driers on large scale and individually owned driers dot the area. Bins are common for storage to wait out the best price for rice. Warehouses were replaced by wooden, then concrete, then steel bins. 1948 was the peak-year for conversion. At the drier, rice sifted through screens to remove chaff, then moved to an elevator by a turn table and fell into small bins that were rotated in intervals over air to not burn or check grain. Then rice was moved back to the bin, aerated, cooled, sampled, and sold.

Horse teams and rail were the old way. Now trucks do it all. When combines and rice carts began harvesting rice, beds of trucks were walled up with a 6-inch trap door at the back for unloading at the drier. A hoist attached to the front end of the truck lifted the truck to unload the truck bed. By the 1960’s, trucks had hydraulic lifts and could hold 100 barrels. About 1945, the rice cart, which was pulled by tractor, joined the combine. Early on, a 32-barrel cart with a 9-inch conveyor emptied in two minutes. By 1969, carts held 45-65 barrels, had adjustable augers, a clutch, reversible treat tires, and heavy drive shafts.

In 1945, the age of planting seed by airplane was born. The practice was not widespread, but it had begun. By 1950, 5% of farms were seeded by air; by the 1960’s, only 5% of farmers did not. Planes flew down to 15 to 20 feet above the ground at about 80 miles per hour and dropped seed in 60-feet strips in one pass. The plane could plant 20-40 acres of seed in an hour. The seeds were dropped into a prepared bed. By the time seeding was done by the air, seed had begun getting chemical treatment and Honduras and Japanese seed had been retired. By 1950, growers began to specialize in growing certified seed rice, which took special care at all phases and examined by a state seed analyst. Seed development became a part of the industry looking to increase its yield. Seeds were dropped on dry and wet fields, trying to develop the best methods. Now, planes drop sprouting seeds on wet fields.

While rice has been the staple crop for farmers in Jeff Davis Parish for a long time, other crops have been grown for profit too. Other crops include hay, sugar cane, cotton, Irish potatoes and sweet potatoes, oats, corn, and soybeans.

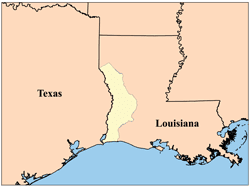

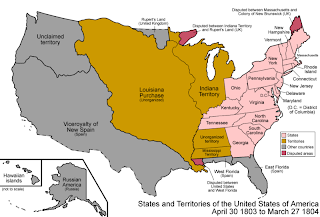

With over eight hundred thousand square miles, the United States subdivided the Louisiana territory to make governing easier. In 1804, the United States formed the Orleans territory with a northern border on the thirty-third parellel, the eastern border on the Mississippi River, the southern border on the Gulf of Mexico and the western border at the Sabine River. On April 10, 1805, the Orleans Territory was divided into 12 counties, including Opelousas County. Spain, however, claimed the lands within Opelousas Territory were still within its border and that its border with Louisiana was the Red River. The Treaty of San Ildefonso had neglected to draw a definite border.

With over eight hundred thousand square miles, the United States subdivided the Louisiana territory to make governing easier. In 1804, the United States formed the Orleans territory with a northern border on the thirty-third parellel, the eastern border on the Mississippi River, the southern border on the Gulf of Mexico and the western border at the Sabine River. On April 10, 1805, the Orleans Territory was divided into 12 counties, including Opelousas County. Spain, however, claimed the lands within Opelousas Territory were still within its border and that its border with Louisiana was the Red River. The Treaty of San Ildefonso had neglected to draw a definite border.